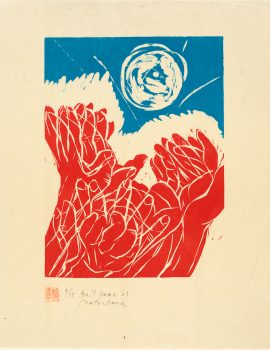

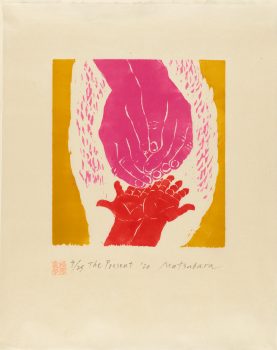

The celebrated 84-year-old artist imbues a reverence of nature to her woodcut art

By Kelly Putter

That elements of nature impart a sweeping backdrop of inspiration for renowned woodcut artist Naoko Matsubara should come as no surprise.

Matsubara became aware of nature’s influence as a youngster living in Japan on a hilltop surrounded by stately, ancient trees. Her father was a Shinto high priest, whose status in the community imbued her with reverence, discipline and a keen, watchful eye. Nature is held in high regard within Shintoism and that belief was not lost on Matsubara. “We have trees that are 2,000 years old and they are considered almost godlike,” she says. “You feel religion in the mountains there because it’s so exquisitely beautiful. I look at nature almost with worship, as if I am in awe of how majestic it is. I do believe that there is some super invisible power in the amazing scale of nature that we still don’t know.”

At 84, the Oakville resident, whose artwork is in major public and private collections around the globe, is still going strong. During the time of COVID Matsubara assumed she would simply fill her isolation with “work, work, work” but sad emotions overtook as she realized that she would not be able to see her son, a graphic artist living in New York City and her cherished granddaughter, who at nine is emerging as a “talented”artist.

So Matsubara, who is also a book illustrator, lecturer and writer in both English and Japanese, redirected her melancholy. She emptied her heart and soul into her artwork for a book about ancient Japanese poems by creating accompanying visual renderings made in her unique woodcut style. Very simply described, woodcut art is akin to the kind of print you may have carved on a potato as a child.

Matsubara was introduced to printmaking in the late 1950s while studying at the Kyoto Academy of Fine Art. A Fulbright scholarship took her to the U.S. where she further studied the ancient woodcut art form at the Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh. There she worked as personal assistant to the late Fritz Eichenberg, a world-renowned printmaking professor and she also taught at the Pratt Institute of Graphic Art in New York, as well as at the University of Rhode Island. She met her husband David Waterhouse, a University of Toronto professor of East Asian studies, in the U.S. and followed him to Oakville, where she has lived for the past 50 years. Since 1960, she has had more than 75 solo exhibitions, in the U.S., Canada, Japan, England, Ireland, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Holland and Mexico.

A distinguished print artist known for creating cheerful and original work, Matsubara continues to surprise, re- invent and push the limits. Even her technique of carving wood to create her images is unique. She is known for her liberal use of a chisel, though has also used traditional gouges, electric power tools and kitchen scissors or a pizza cutter to create her designs. Nature may be a major influence, but she is also inspired by literature, music, movement and place. In her early career, she often used black and white and would later expand to colour. Abstract, figurative, collage have comprised much of her artwork. Matsubara has used carved and coloured wood blocks to create murals in which the medium itself becomes the artwork.

Two of her murals will be on display in Oakville, one is currently at the YMCA and the other is scheduled to be displayed at Oakville Trafalgar Hospital. A mural hangs in the main hall of the St. Catharines Kiwanis Aquatics Centre, the city’s first commissioned work of public art. For these monumental projects, she works on half-inch-thick pieces of wood that are about 12-by-12 inches square. The squares are hung on the wall and Matsubara has a ladder from which she can paint the squares in her at-home studio. The squares are framed with a backing and then they are arranged into massive wall designs. She especially likes that her murals are permanent exhibits available for public viewing.

But are these immense endeavours difficult for an octogenarian? Not really. Labour and time doesn’t much weigh on her. The first mural took her a year though she’s done others in much less time. When working, she’s more focused on the innovation and creativity of a project. “I like making something no one has ever done,” says Matsubara. “And I like when people look at it and feel happy or invigorated or moved. But I am my own worst critic. That’s how you grow, though.”