By Kelly Putter

Remnants of the cowboy persona Steve Driscoll created as an up-and-coming artist inform his work today, some 20 years after the Stetson, bourbon and cigarettes he sported as an unknown artist trying to make his mark.

“When I was in my twenties, friends thought I was in my forties because I wore a cowboy hat and boots and smoked my life away,” says the 41-year-old Oakville born artist whose widely acclaimed work is, among other things, a clear cowboy-esque nod to the rugged Canadian outdoors. “It was all part of my art persona. Students get certain personas in art school as a means to build up your ego.”

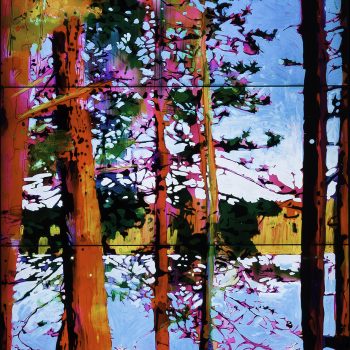

As a noted Toronto-based artist, Driscoll’s work speaks for itself. Mythic, western references aside, Driscoll is known for arresting larger-than-life nature pieces often rendered in a trippy kaleidoscope of neon colours. The effect is decidedly majestic, awesome and whimsical. It makes sense that he’s equally inspired by Gauguin and GoPro as he draws from the tradition of nature with the help of the modern world.

His most recent opus is a massive public art installation called A Light Stolen from the Sun, which features 12 mammoth works that are backlit on laminated glass in the main lobby and fourth-floor mezzanine of one of the towers of the new CIBC Square located in Toronto adjacent to Union Station that will, in 2024, house two towers totalling 3 million square feet and an elevated park open to the public.

Inspired by Canada’s boreal forest, the paintings took over five years from start to finish. Using an unusual mix of urethane tinted with oil paints, Driscoll was able to achieve the intense colours he was after. Digitizing the artwork came next as every square inch was documented in close-up and then put back together into one huge digital file. The image was printed onto glass which was then laminated onto a second piece of glass, serving to sandwich the image between the two pieces of glass. The glassworks were so heavy and awkward that a hoist was needed to fit them into place. The main lobby houses six panels, each 36 feet high by nine feet wide. Another six panels are situated in the lobby of the fourth floor where 16 feet high by nine feet wide backlit pieces give viewers the perspective of looking up inside a forest canopy.

Much of his inspiration harkens back to his cowboy aesthetic. The married father of two loves camping, canoeing and hiking – the outdoors in general, the Bruce Trail specifically especially with his dog Nellie in tow. Add to that his curiosity about the mixing of materials and you have an artist destined for experimentation, novelty and surprise. Born on the millennial cusp, Driscoll understands technology and is continually intrigued by how humans examine nature thanks to social media.

Colour is a motivator, especially saturated, intense colours thanks to Driscoll’s love of post impressionists. The Ontario College of Art graduate uses colour to express emotions in his work rather than mimicking realistic shades of nature. “If you take a picture of the woods, it’s gray and brown but the memory of walking in the woods won’t look like that,” he explains. “My colours represent the memory of a place rather than an actual place. We have emotional connections to things and that’s how we remember them. I prefer to bring out the emotional quality or essence of the thing rather than the thing.”

A prolific artist who signs on for three to five art shows annually, creating 12 to 20 new pieces per show, Driscoll might be labelled a workaholic but he’s comfortable with the affliction. “I’m working nine to five every day,” he says, though the pandemic has slowed things somewhat. “I like the practice of painting. I like working. I go on vacation and feel anxious about not being in the studio.” Upcoming shows this year include the Peter Robertson Gallery in Edmonton in February and Toronto’s Nicholas Metievier Gallery in April.

Though he previously worked at several jobs in the housing industry – appraiser, construction – to support his art in his early days, Driscoll is a testament to creatives who manage to make a living through their art. He admits a wee annoyance with the starving artist narrative. “There is this preconceived notion that all artists are starving and crazy and desperately in need of support when there is this whole industry of artists who market art and ship it around the world. They are professionals working everyday and trying to engage with culture. Artists are journalists and we react to things around us and add to visual culture.”

Driscoll’s work has been exhibited in New York, Europe and Canadian galleries from coast to coast. His work is included in museum collections including the McMichael Canadian Art Collection as well as earlier pond exhibitions in which Driscoll flooded gallery floors with water while building a bridge so gallery goers could view his paintings. Numerous corporate, hospital and bank collections also include his work.